There was a record number of Houston traffic deaths last year, solidifying the city’s reputation as one of the most dangerous places in the nation for drivers, passengers, and pedestrians. According to a recent article in the Houston Chronicle, 345 people died on city streets in 2024 – an alarming 15 percent increase from the year before.

This is not just a statistic—it’s a crisis. Every one of these deaths represents a family left devastated, a community left mourning, and possibly a preventable tragedy that should have never happened. If someone you love has been killed on a Houston-area street, it’s imperative to contact an experienced Houston personal injury attorney as soon as possible.

In this article, our wrongful death attorneys discuss the primary causes of Houston traffic deaths, including pedestrian accidents, who can be held liable, and what family members should do to seek justice and compensation when tragedy strikes. But first, please watch this video by Ty Stimpson, who leads Varghese Summersett’s personal injury team.

Common Causes of Houston Traffic Deaths

Houston’s roads have become increasingly deadly, with a record number of traffic fatalities reported in 2024. Understanding the root causes of these tragedies is critical to preventing future accidents and holding negligent parties accountable. The most common causes of Houston traffic deaths include:

1. Drunk and Impaired Driving

Driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs continues to be one of the leading causes of fatal crashes in Houston. Impaired drivers have reduced reaction times, impaired judgment, and an increased likelihood of making deadly mistakes behind the wheel.

2. Speeding and Reckless Driving

Excessive speed is a major factor in fatal accidents, as it reduces a driver’s ability to react to sudden hazards and increases the severity of collisions. Reckless driving, such as aggressive lane changes, tailgating, and street racing, also contributes to the rising death toll.

3. Distracted Driving

With smartphones, in-car entertainment systems, and other distractions, many drivers are not fully focused on the road. Texting, talking on the phone, and even adjusting GPS settings can take a driver’s attention away for just a few seconds—often with deadly consequences.

4. Poor Road Conditions and Infrastructure Issues

Houston’s rapid growth has led to congested highways, poorly designed intersections, and dangerous pedestrian crossings. Inadequate lighting, potholes, and missing or unclear traffic signs also play a role in fatal accidents.

5. Pedestrian and Cyclist Vulnerability

Houston has long struggled with pedestrian safety. Many areas lack proper crosswalks, sidewalks, or bike lanes, forcing pedestrians and cyclists to navigate dangerous roadways. Drivers who fail to yield or watch for non-motorists contribute to the rising number of pedestrian and bicycle fatalities.

6. Running Red Lights and Stop Signs

Intersections are among the most dangerous places on Houston roads. Many fatal crashes occur when drivers run red lights, ignore stop signs, or fail to yield the right of way—often at high speeds.

7. Weather-Related Crashes

Houston’s unpredictable weather, including heavy rain and flash flooding, makes driving conditions hazardous. Many drivers fail to adjust their speed for wet or slick roads, leading to hydroplaning and loss of control.

8. Drowsy Driving

Fatigue-related crashes are on the rise, particularly among truck drivers and shift workers. A drowsy driver’s impairment can be just as dangerous as a drunk driver’s, with slowed reaction times and an increased risk of falling asleep behind the wheel.

9. Failure to Wear Seatbelts

Seatbelts save lives, but many fatal crashes in Houston involve passengers who were unrestrained. Not wearing a seatbelt significantly increases the likelihood of severe injury or death in a crash.

As Houston continues to grow, so does the risk on its roads. While many of these accidents could have been prevented, those responsible must be held accountable. If your loved one has been killed in a Houston traffic accident, an experienced personal injury attorney can help you pursue justice and compensation.

Houston Pedestrian Fatalities

In 2024, Houston experienced a significant increase in pedestrian fatalities, with 119 pedestrians losing their lives on city streets—a substantial portion of the 345 total traffic deaths that year. Notably, more than half of these pedestrian fatalities occurred on roads with speed limits of 45 mph or higher, and 44 pedestrians died on Houston interstates, surpassing the 43 driver fatalities in the same areas.

Several factors contribute to the high rate of pedestrian fatalities in Houston:

- High-Speed Roadways: Many pedestrian deaths occur on high-speed roads where crossing safely is challenging due to fast-moving traffic.

- Infrastructure Deficiencies: The absence of adequate crosswalks, sidewalks, and pedestrian signals forces individuals to navigate dangerous areas without proper safety measures.

- Driver Negligence: Incidents of drivers failing to yield, speeding, or driving distractedly significantly increase the risk to pedestrians.

- Limited Lighting: Poorly lit streets make pedestrians less visible to drivers, especially during nighttime hours.

In response to the rising number of pedestrian fatalities, the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) launched the “Be Safe. Drive Smart” campaign in October 2024. This initiative aims to encourage drivers to slow down and remain vigilant for pedestrians, particularly during months with reduced daylight.

Despite these efforts, pedestrian fatalities remain a critical concern in Houston. If someone you love has been killed in a pedestrian accident, it’s essential to consult with an experienced Houston personal injury attorney to explore your legal options and seek justice for your loss. We offer free, no-pressure consultations. We also work on contingency, which means you only pay after we win your case. You will never pay anything upfront or out-of-pocket.

Legal Options for Victims and Families

When a loved one is killed traffic accident due to someone’s negligence, families have legal options to seek justice and compensation. At Varghese Summersett, our Houston personal injury attorneys fight for victims and their families in cases involving negligent drivers, unsafe road conditions, and corporate liability. Understanding the available legal avenues is crucial for ensuring accountability and financial relief during an incredibly difficult time.

Wrongful Death Claims in Houston Traffic Fatalities

Under Texas Civil Practice and Remedies Code §71.002, certain family members—including the spouse, children, or parents of the deceased—can file a wrongful death lawsuit against the party responsible for the fatal accident. A wrongful death claim seeks to compensate surviving family members for their profound loss. Potential damages may include:

- Funeral and burial expenses

- Lost financial support and income that the deceased would have provided

- Loss of companionship and emotional support

- Emotional pain and suffering endured by surviving family members

These claims are designed to hold negligent drivers, government agencies, and corporations accountable when their actions or inaction result in tragic and preventable fatalities.

Elements Required to Prove a Wrongful Death Claim in a Houston Traffic Death

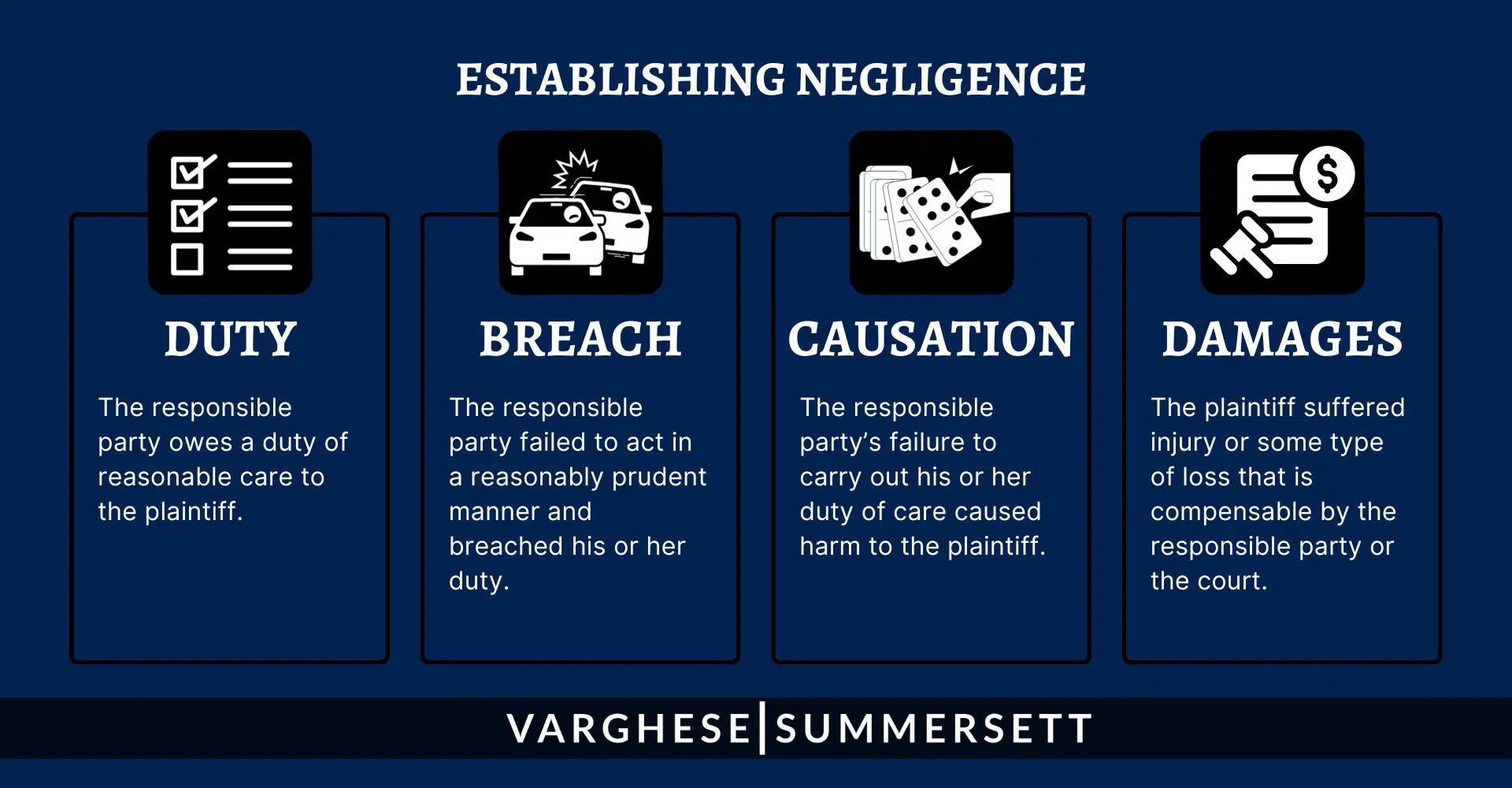

To successfully pursue a wrongful death claim, the following four key elements must be established:

Duty of Care – The defendant (such as a negligent driver, trucking company, or government agency) had a duty to operate their vehicle or maintain the roadway in a safe and responsible manner.

Breach of Duty – The defendant failed to uphold this duty by acting negligently or recklessly, such as by speeding, running a red light, driving under the influence, or failing to provide safe pedestrian crossings.

Causation – The defendant’s actions or negligence directly caused the fatal accident. This may require evidence such as police reports, witness statements, and accident reconstruction analysis.

Damages – The family has suffered significant losses, including financial hardship, emotional distress, and other damages as a result of their loved one’s death.

Proving these elements requires thorough investigation, expert testimony, and a strong legal strategy, which is why having an experienced Houston wrongful death attorney is essential.

Survival Claims in Houston Traffic Fatalities

In addition to a wrongful death claim, Texas Civil Practice and Remedies Code §71.021 allows the victim’s estate to file a survival claim. Unlike wrongful death claims, which compensate surviving family members, a survival claim seeks damages on behalf of the deceased for losses they suffered before passing away.

These damages may include:

- Medical expenses incurred before death

- Pain and suffering endured before passing

- Lost wages if the victim survived for a period after the accident but later succumbed to their injuries

Survival claims ensure that the at-fault party is held accountable for all consequences of their actions, even if the victim did not pass away immediately.

Third-Party Liability in Houston Traffic Deaths

While many wrongful death cases focus on individual drivers, third parties may also bear responsibility for a fatal accident. Potential third-party claims include:

- Commercial or trucking companies – If a negligent truck driver caused the crash while working, their employer may be liable.

- Bars or establishments – Under Texas Dram Shop laws, businesses that over-serve alcohol to an already intoxicated person who then causes a fatal crash may be held responsible.

- Government agencies – If unsafe road conditions, poor traffic control, or a failure to maintain roadways contributed to the accident, the city or state could be liable.

- Auto manufacturers – If a vehicle defect, such as faulty brakes or airbag failure, played a role in the crash, the manufacturer may be legally responsible.

Identifying all responsible parties is crucial to maximizing compensation and ensuring full accountability.

What to Do If Your Loved One Was Killed in a Houston Traffic Accident

Losing a loved one in a sudden traffic accident is heartbreaking, and the emotional toll can be overwhelming. While no amount of compensation can bring them back, taking the right legal steps can help protect your family’s future and ensure those responsible are held accountable. If your loved one was killed in a Houston traffic accident, here’s what steps to take:

- Obtain a Copy of the Police Report – This document is essential for understanding the details of the accident, including statements from witnesses and any citations issued to the at-fault party.

- Preserve Evidence – If possible, collect photos and videos of the accident scene, vehicle damage, road conditions, and any other relevant factors. Surveillance footage, dashcam recordings, and 911 call logs can also provide critical evidence.

- Identify Witnesses – Witness testimony can be crucial in determining fault and strengthening your claim. If anyone saw the accident happen, try to get their contact information.

- Consult an Experienced wrongful death Attorney – A skilled Houston wrongful death lawyer will handle every aspect of your case, from investigating the accident to negotiating with insurance companies and pursuing legal action if necessary. They will work tirelessly to secure the compensation your family deserves.

- Don’t Speak with Insurance Adjusters Without Legal Representation – Insurance companies often attempt to minimize payouts or shift blame. Let your attorney handle all communications to ensure your rights are protected.

- Take Action Quickly – Texas law imposes a strict two-year statute of limitations on wrongful death claims. Failing to act within this timeframe could jeopardize your ability to recover compensation.

Navigating a wrongful death claim can be complex, but you don’t have to go through it alone. Contact our Houston wrongful death attorneys today for a free consultation. We will guide you through the legal process and fight for justice on behalf of your loved one.

Get the Justice Your Loved One Deserves – Contact Us Today

Losing a loved one in a preventable traffic accident is devastating, but you don’t have to face this fight alone. At Varghese Summersett, our compassionate and experienced wrongful death attorneys will stand by your side, guide you through the process, and pursue the justice and compensation you deserve for the death of your loved one.

Call us today for a free, no-obligation consultation. We will thoroughly evaluate your case, explain your legal options, and take immediate action to hold the responsible parties accountable. Your family’s future matters—let us help you protect it.